Hello everyone!

Del here. Welcome to the second installation of the Intersectionality Primer.

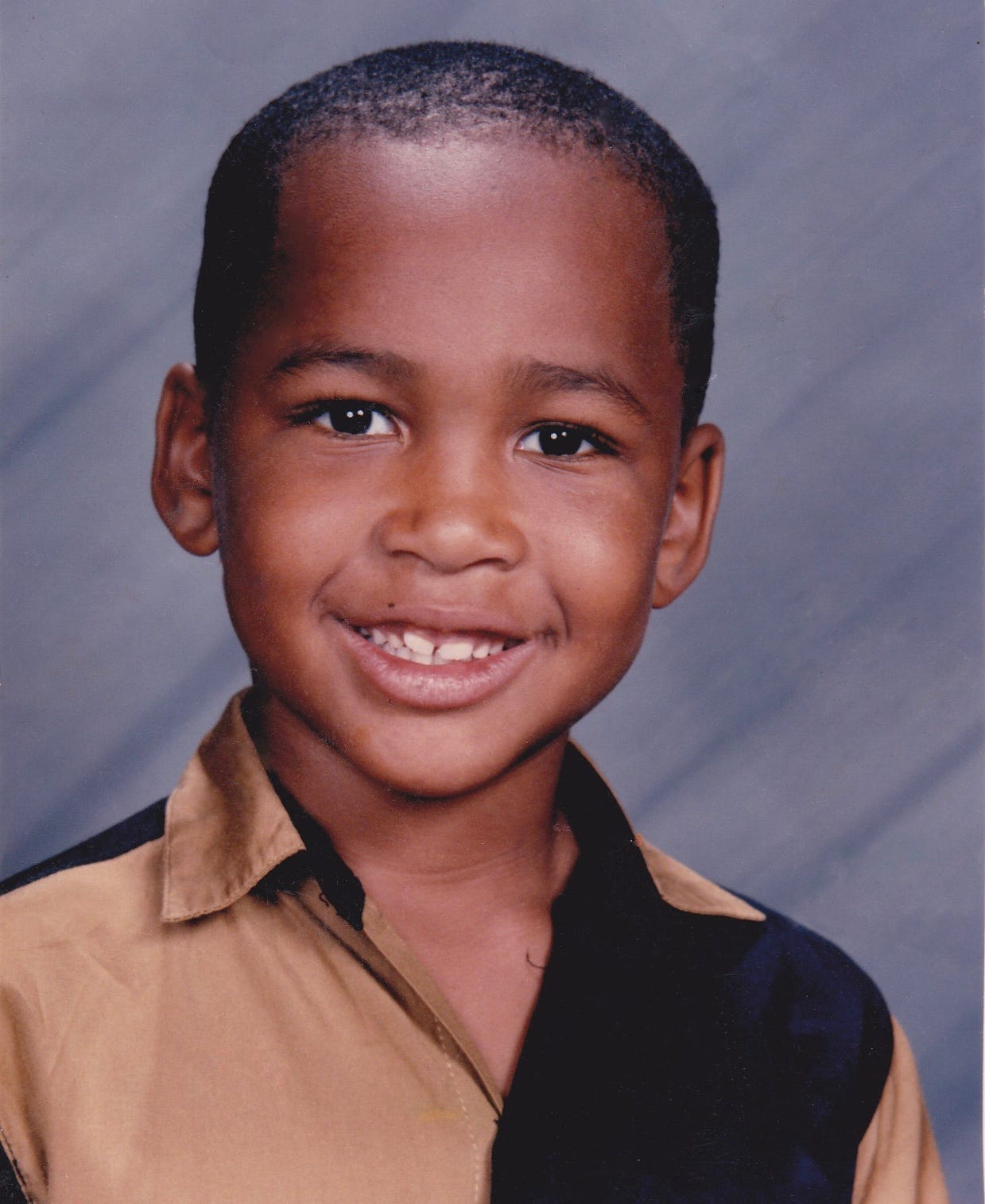

I learned early in life that there are things you can’t do as a Black boy that other children can. There are places that you can’t go. There are road trips you politely decline and friends who will never introduce you to their parents. There are employers you know will never hire someone who looks like you. Though you rarely get an explanation for the disparate treatment, you don’t need one.

You might have recently heard about “The Talk” that Black parents have with their sons. Our parents prepare us for police encounters and maneuvering spaces in a Black male body at an early age. For Black men, the discussion extends into every facet of our lives.

Despite my desire to dismantle this status quo, there are still things I don’t do, because the possible consequences could endanger my life. At night, when I see a white woman walking in the same direction as me, I might preemptively cross the street. If crossing is not an option, I drag my feet, making noise as if to say, “Nothing threatening here, just trying to get home!” I can’t risk a misunderstanding that turns into an encounter with the cops.

You Don’t Belong, Even if You Do

As Black men in the workplace, society and experience teach us to dress conservatively. We become masters at toeing the line between assertive and non-threatening. We learn to stay quiet about race even when that silence damages our career prospects. We do it for survival. But all of the personal constraints in the world don’t stop the surveillance and suspicion that comes with moving through life as a Black man.

Two years after I finished my contract work at Google with distinction, I was back in the lobby of the Google New York office as a visitor. I remember meticulously following the check-in instructions. I remember asking the desk attendant twice if my entry pass was valid and watching the gate open as I scanned the QR code. I remember, because I knew this was a situation where bodies like mine are policed.

Even though I did everything by the book, a security guard still confronted me as countless other visitors passed by without issue. Here we go again. He questioned whether the entry badge I printed just seconds earlier was legitimate. He doubled down on his disbelief when I flashed him my pass. We exchanged sharp words, causing a small commotion. Then, the next thing I knew I was being waived into the building by another employee who seemed to appear out of nowhere. No harm done, except to my ego, I thought. When your body looks a certain way, you don’t belong, even if you do. That's the price of doing business in this country.

An “Understandable” Reaction?

Do you remember how the “L.A. Riots” started? If the name Rodney King comes to mind, you’re partially correct. But, the acquittal of the four police officers who beat King on camera is only part of the story.

On March 15th, 1991, Soon Ja Du, a Korean woman who owned a convenience store, shot and killed a 15-year-old Black girl named Latasha Harlins. Du claimed that Latasha had stolen a $1.79 bottle of orange juice from the store, but security footage showed Latasha walking toward the register with the money to pay for the juice in her hand.

At Du’s trial, the jury recommended imposing the maximum sentence of sixteen years. The judge, Joyce Ann Karlin, rejected the jury’s guidance saying, “Did Mrs. Du act inappropriately? Absolutely. But was that reaction understandable? I think that it was.”

She instead sentenced Du to 400 hours of community service, 5 years of probation, and a $500 fine. For 6 days, the city went up in flames.

Black Bodies & the Bodega

Stockwell, a “smart” vending machine company dubbed “the most hated startup in America” shut down last week. Much of the tech community hated Stockwell, but I couldn’t muster the same anger and indignation. Given the devaluation of Black voices in tech, it doesn’t surprise me that perspectives like mine weren’t centered in debates about the company.

I agreed with many of the tech community’s critiques of Stockwell. Yes, the company's original name, “Bodega,” was plainly offensive. Yes, their stated mission of “disrupting” mom-and-pop corner stores was an affront to hard-working immigrant entrepreneurs. Yes, $45 million was a lot of money to invest in a business with little traction.

Growing up in a lower-class Black community in California, I saw the corner store as a site of constant surveillance, harassment, and embarrassment for Black patrons. Store owners routinely watched us, accused us of stealing, and accosted us.

I think about how much Black death has occurred in proximity to the corner store. I think about Mike Brown and the cigarillos, Travon Martin and the Skittles, George Floyd and the $20 bill. I think about Latasha Harlins, and I can’t help but wonder if something like Stockwell could offer an alternative to risking death for a $1.79 bottle of orange juice? And if so, maybe a little disruption wouldn’t be such a bad thing.

With that, we’ll turn to this week’s topic with Nisreen.

- Del

What Makes a Group Intersectional?

Last week we introduced intersectionality and the concept of “demarginalizing.” We learned how demarginalizing, or centering, an intersectional group like Black women can reveal harms that might otherwise go unnoticed. We figured out which groups to demarginalize by considering “what difference a difference makes.” This means we used evidence to explain what it is about a certain group of people that justifies their centering in a particular analysis.

This week we ask, what constitutes a “group” for the purpose of an intersectional analysis? Is identity an essential aspect of a person? Is it socially constructed? In what ways will these distinctions matter? We will consider these questions through the lens of Black men and Black masculinity.

The “Chokehold”

Paul Butler, Georgetown University Law professor and former prosecutor, takes us through the construction of Blackness in Chokehold, his book on police violence. Butler goes beyond the literal definition of a chokehold, defining The Chokehold as:

“[A] way of describing law and social practices designed to respond to African American men. It is a two-step process. Part one is the social and legal construction of every Black man as a criminal or potential criminal. Part two is the legal and policy response to contain the threat.”

Although Butler’s analysis focuses on Black men, notions of Blackness have often been transitory. The experience of European immigrants highlights this phenomenon.

In the late 1800s when a sudden influx of Italian immigrants came to the Southern United States, Southerners initially welcomed the immigrants because the Italians were willing to work for the same low wages landowners paid to newly freed slaves. Northerners derided Italian immigrants as “links in a descending chain of evolution” and “ a new population of Negros.”

Now, most Americans consider Italians to be white. Italians “escaped” their grouping into Blackness through active measures. This process started with the assassination of the New Orleans police chief in 1890. The police charged nineteen Italian residents with murder on the word of a dubious witness. When most of the arrestees were acquitted, a mob went after the Italians and lynched them.

In retaliation to the lynchings, the Italian government broke off diplomatic relations with the United States. President Benjamin Harrison then began to make amends to the Italian community by recognizing the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus as the “first immigrant” to “discover” what would eventually become the United States. This inaccurate rewrite of history “granted Italian-Americans a formative role in the nation building-narrative.”

Only a century after arriving in America, sustained public pressure applied by the Italian community both internationally and domestically successfully granted Italian Americans their place as white Americans. Italians were thus granted the legal and social privileges that came with whiteness, while the subjugation of Black people continued.

Are Black Men Intersectional?

Let’s pause here to consider the link between identity and intersectionality. As Del mentioned, being under constant surveillance and suspicion continues to be a feature of being a Black man in America. If we accept that surveillance is a particular experience of the Black male intersection, we might consider the combination of Black and man as an intersectional category.

As you may remember from last week, Kimberlé Crenshaw contrasted Black men with Black women. She concluded that in the context of legal discrimination (as in Degraffenreid v. General Motors), Black men were not an intersectional group because Black men did not face the combined racism and sexism Black women faced.

Butler addresses this head on:

“To observe that the experiences of Black men are determined by their race and gender does not mean that their plight is worse than that of some other groups, particularly African American women.”

Butler argues that the subjugation of Black men in America, while not necessarily worse than the subjugation of Black women, takes both a gendered and raced form. Specifically, Black men can be punished because they are men and Black. Thus, he concludes, intersectionality “creates a space” for a Black male analysis.

Black Masculinity and the Chokehold

The United States has a history of perceiving Black male bodies differently and thus subjecting those bodies to controls as a result of that difference.

Lynching, or the extrajudicial killing of a person, has frequently been used to keep Black men under control and justified through the protection of white womanhood. In her book Southern Horrors, Ida B. Wells, a Black woman reporter and anti-lynching activist summized, “White men used their ownership over the body of the white female as terrain on which to lynch the Black male.”

In one of the most famous and tragic cases of the 20th century, Emmett Till, a 14 year old boy, was lynched by a mob after a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, falsely accused him of whistling at her outside of a grocery store.

Differential treatment for Black men continues to this day. Butler notes that policies like “stop and frisk” demand a certain kind of “performance” from Black men every time they leave the house to demonstrate that they are “not a threat.”

Erroneous beliefs about Black men’s physical differences persist as well. In 2017, former Los Angeles police chief Daryl Gates, “suggested that there is something about the anatomy of African Americans that makes them especially susceptible to serious injury from chokeholds, because their arteries do not open as fast as arteries do on ‘normal people’”.

Let’s pause here for a moment and think about “demarginalizing.” Given what you’ve learned about intersectionality, does Butler argue successfully that Black men are an intersectional group? What difference does difference make to Black men in America when it comes to issues like policing? Does the experience of Italian immigrants give us hope that Black masculinity can escape the harmful constructions of the chokehold and be reformed or dissociated from Black male bodies? Is this the question we should be asking?

Policing Black Masculinity in Black Female Bodies

While Paul Butler makes a strong argument for including Black men in the intersectional framework, Crenshaw asks us to consider the ways society imposes Black masculinity on Black women.

Similar to tropes about Black men, the idea of Black women as subhuman continue to persist into the 21st century. In 2016, a white woman in West Virginia made headlines when she referred to First Lady Michelle Obama as an “ape in heels.” Three years prior, comedian Roseanne Barr called former National Security Advisor Susan Rice an “ape.”

Scholars have noted the ways murders of Black women like Latasha Harlins call back to the idea of the dangerous Black man.

“[B]lack women in American society traditionally have been stereotyped by nonblacks as being more like “men” than “women”...In this particular case, while Latasha became masculinized in the defense attorney’s rhetoric, Du’s image took on some of the exaggerated feminine characteristics...In Judge Karlin’s estimation, Du was only defending herself against a real threat, the threat of the vicious, uncontrollable “black beast.””

- Brenda Stevenson, The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins

Although Black men face the chokehold in particular gendered ways, Crenshaw reminds us that intersectionality is not just about the assertion of difference, but exploring what difference that difference makes to a particular project.

When using an intersectional lens to evaluate policing and surveillance, Crenshaw finds that the chokehold also endangers Black women and girls. Perceptions of Black masculinity harm all Black people including Black women. Yet the danger to Black women often goes unnoticed or ignored by activists, media, and policymakers.

As you can see, “doing intersectionality” doesn’t necessarily mean scholars arrive at the same conclusions. But that is exactly why applying an intersectional lens is critical to considering what groups must be demarginalized. It takes ongoing, deliberate analysis.

While Butler and Crenshaw arrive at different conclusions in their intersectional analysis of Black men and Black masculinity, one thing is clear: it is time to stop ignoring all the ways Black women have been policed, surveilled, and killed.

This week’s newsletter is dedicated to Breonna Taylor. #SayHerName

- Nisreen

Reflection

Crenshaw argues that programs for Black people like professional development and youth intervention (think: President Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative) often focus on Black men to the erasure of Black women. In your workplace, have you seen a similar prioritization of Black men’s issues over Black women? Have programs in your own workplace failed to consider the specific experiences of Black women? If so, what policies or programs would you create to address the disparities?

Read about the events that led to the killing of Rayshard Brooks. Take note of the police officers’ interactions with Brooks. Using what you have learned about perceptions of Black masculinity, break down what you think is behind the police officers’ decisions to escalate the situation to its tragic end. Are there specific moments in which you think the police officers could have deescalated the situation?

In the Chokehold, Butler discusses a 2016 study of arrestees in Minnesota which found that white men with Afrocentric features (e.g. larger lips and/or full noses) “were more likely to get punished than other white men.” Does the concept of the chokehold explain this phenomenon? Think about your social and professional spheres. Have you ever noticed anything similar?

Resources

Chokehold by Paul Butler

The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins by Brenda Stevenson

Black Masculinity and the US South by Riché Richardson

P.S.

At the Intersectionality Primer, we stand against police brutality. This week, in addition to completing the reflections, we ask that you consider making a donation to one of the following organizations:

We’re taking a break next week. See you after the holiday! Until then, follow us on Twitter at @nisreenhasib and @deljohnsonvc