Intersectionality: A Special Report on "Karen"

White Feminism and its Critics

Hello everyone!

Welcome back to the Intersectionality Primer. And now, a special report on Karen:

None of the editors of the Intersectionality Primer are white women. We cannot tell you what it’s like to live and work as a white woman—to be seen as carrying that particular combination of privilege and deprivation. But as we review the recent media coverage of “girlbosses” and “Karens” behaving abusively, we can’t help but notice what isn’t there. Stories of regular people who face the brunt of the abuse usually go untold. Often those harmed are other women or women of color whose voices easily get lost.

An article about a woman founder who yells at her employees becomes a small part of a broader narrative about tech executives versus the media. Stories of white women calling the police or pulling guns on Black people become about whether using the term “Karen” is a slur.

While we may not know what it feels like to be a white woman, we have all been affected by societal conceptions of white womanhood. If you’re a woman or minority in tech, you might have even found yourself grappling with “feminism” or encountering “Karens” in everyday interactions. How should we be analyzing these situations as students of intersectionality? How can we tell if someone is replicating repressive systems—or if our own biases might be clouding our judgment? This week, we dive into ongoing debates on female representation, the trope of the “Karen,” and the role of race in feminism.

Misrepresenting female founders?

“That was jarring—three white people telling me [a person of color] I was racist,”

- Former Away Employee

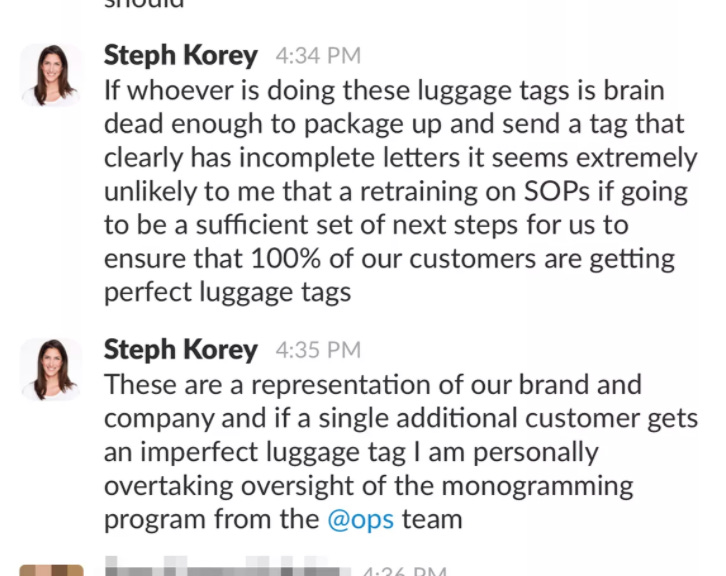

In December 2019, employees at the direct-to-consumer luggage startup Away accused then-CEO Steph Korey of fostering a toxic work environment. They claimed that Korey’s management style, centered on a culture of “transparency,” instead produced a culture of intimidation and surveillance that negatively affected underrepresented workers. In one incident, Korey is alleged to have fired six employees for conversations held in a private, LGBTQ and POC centered Slack for messages she deemed, “hate speech.” Other employees cited a pattern of verbal abuse saying, “You could hear her typing and you knew something bad was going to happen.” For example, Korey allegedly took to Slack to call out “brain dead” workers, and later indicated that poor-performing employees should forego taking vacation:

For many onlookers the allegations were disheartening. Korey had been a champion of women founders and was linked to the broader “girlboss” movement—a group of prominent female founders who claimed that their presence and power was changing tech for the better. Korey’s alleged hypocrisy—publicly evangelizing female representation but insufficiently protecting women at her own company—was said to be proof of the movement’s failure. As The Atlantic explained, “For the girlboss theory of the universe to cohere, women have to be inherently good and moral creatures, or at least inherently better than men…”

Meanwhile, Korey’s defenders pointed out that her behavior wasn’t atypical for the high-pressure world of venture backed startups, and that comparable male behavior would have been a “non-event.” Were Korey’s detractors, including female members of the media, perhaps giving her and other female founders a harder time because they were woman? Korey seems to have thought so.

Recently, she took to Instagram to question the media’s motives in what she saw as the unfair targeting of female founders. She wrote that journalists were, “...knowingly misrepresenting female founders for clicks & their own profile/fame.”

Employees once again objected to Korey’s statements. In the midst of nationwide protests in support of Black Lives Matter and Pride month, they argued that her statements were distracting and harmful.

Tech and VC Twitter erupted in defense of Korey, launching a battle that included alleged harassment of a female journalist, the exposure of private information of a prominent investor, and digital currency meme bounties. Days later, pictures of Korey dressed as a Native American surfaced on Twitter. Under mounting pressure, Korey announced that she was once again stepping down as CEO for the second time in under a year.

Given that society (broadly) does not perceive women in power favorably, did Korey have a point in calling out what she sees as biased media portrayals? Or is her argument simply a distraction from the real story of abusive behavior towards her minority employees? With that, we begin our dive into feminism.

-The Intersectionality Editorial Team

When Difference Makes No Difference

In our last newsletter, we asked what constitutes a “group” for the purpose of intersectional analysis. We studied the social transferability of whiteness through the lens of Italian immigrants in America. We then concluded by asking if Black men could make intersectional claims.

This week, we explore the potential limits of intersectional analysis. When does upholding difference become confusing as opposed to clarifying? We consider this question through the lens of feminism and dominance theory.

What is a “Karen,” Anyway?

"I'm taking a picture and calling the cops...I'm going to tell them there's an African American man threatening my life."

-Amy Cooper

If you have been anywhere near the internet these past few months, you have probably become familiar with the “Karen” meme. Once a stand in for a rude, annoying, middle-aged white American woman who is always asking to “speak to the manager,” a series of racist incidents has elevated the “Karen” into a truly dangerous archetype.

A “Karen” has recently come to be defined by her extreme bias against minorities, especially Black people. It’s a bias that most often manifests as a strong proclivity towards calling the police for mundane transgressions. The most notable recent example of “Karen” in action was Amy Cooper, a financial executive who was caught on camera threatening to falsely accuse a Black man, Christian Cooper, of threatening her. In reality, Christian had asked her to leash her dog in a public bird watching sanctuary.

Everybody Hates Karen

The social backlash against the Karen has been swift and decisive, with many white people even joining in on the condemnations. The backlash has even manifested in the passage of legislation in New York, creating a private cause of action for false 911 calls. Similar legislation in California is called The "CAREN Act" (Caution Against Racially Exploitative Non-Emergencies).

Feminism and Gender Equality

Although the name “Karen” might be new, the Karen archetype has historical precedent. Catherine Mackinnon, feminist theorist and Harvard law professor speaks about the common white woman archetype in her 1991 article “From Practice to Theory, or What is a White Woman Anyway?” Mackinnon describes the white woman stereotype as, “[p]rivileged, protected, flighty, and self-indulgent...She is Miss Anne of the kitchen, she puts Frederick Douglass to the lash, she cries rape when Emmett Till looks at her sideways, she manipulates white men's very real power with the lifting of her very well-manicured little finger.”

As a feminist, Mackinnon argues that negative beliefs about white women ultimately damage the feminist fight for gender equality. By fixating on the privileges that white women have because they are white, critics overlook the real struggles white women face because they are women, namely that “the majority of the poor are white women and their children (at least half of whom are female); that white women are systematically battered in their homes, murdered by intimates and serial killers alike...” Thus, for Mackinnon, to say that white women are free of subjugation because they are white erases a dynamic of womanness that anyone interested in gender equality should take seriously.

To many who identify as “Black feminists,” Mackinnon’s argument rings hollow. We will discuss Black feminism as a movement in a future newsletter, but as a quick overview, much of the Black feminist discourse rose out of a real critique that white feminists had erased the voices of people of color, particularly the voices of Black women, from feminism generally. Even going back to early feminism’s debates in the 1800s about the right to vote, many white feminists, including notable figures like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Caddy Stanton, lobbied against the passage of the 15th Amendment, which extended the right to vote to Black men.

“[The amendment] creates an antagonism everywhere between educated, refined women and the lower orders of men, especially in the South.”

- Elizabeth Caddy Stanton

Encounters with Intersectionality

Professor Crenshaw talks about the lasting aversion to Mackinnon and theories associated with “white feminists” in her paper, “Close Encounters of Three Kinds: On Teaching Dominance Feminism.” The paper details Crenshaw’s struggle of teaching feminist theory to the law students in her Intersectionalities Workshop, of which this newsletter is loosely based. Crenshaw’s social justice oriented students often reject Mackinnon and other “white feminist” arguments for reasons similar to Black feminists.

Their biggest critique against white feminist writing is that it is “essentialist,” meaning that the writing assigns a universal “womanness” to all women that centers the particular, privileged experiences of white women. Black feminism, to the contrary, seeks to center the lived experiences of women of color. According to this line of thinking, white feminism is bad because it lacks an intersectional lens that results in the erasure of Black women.

Crenshaw teaches Mackinnon’s writings in her Intersectionalities Workshop because she sees Mackinnon as one of the only white feminists writers who addresses Black feminism and essentialism head-on, instead of engaging in “superficial gestures of inclusion,” meant to pacify critics. Crenshaw uses Mackinnon’s feminist writings as a lens to investigate instances where students cling to certain assertions and narratives about groups that stand in for “more complex realities.” We know that white women have different life histories, personalities, motivations, etc. So why do the students think it is acceptable to group white women into certain stereotypical groupings (like the trope of the Karen), but push back when people of color are similarly stereotyped?

Mackinnon’s writing attempts to address Crenshaw’s question. Her answer is that Black feminists often fall into their own form of essentialism. They become overly focused on theories of identity over lived experience, and then use those theories to inform their analysis. This means that Black feminists, by focusing too intently on how a white feminist solution might erase Black women, miss instances where the solution could help all women as a class. She concludes by making a recommendation to start all feminist analysis with lived experience and concrete examples. By doing so, all feminists can better understand the true source of female subjugation—male dominance.

“Feminism was a practice long before it was a theory. On its real level, the women's movement—where women move against their determinants as women—remains more practice than theory.”

- Catherine Mackinnon

The Hierarchy of Inequality

Mackinnon illustrates her point through legal examples. She explains how sexual harassment was not seen as “sex based” discrimination under anti-discrimination law until the 1986 case of Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson. It was only when Mechelle Vinson, a Black woman, sued her employer for assaulting her repeatedly, that the courts recognized that women are often harassed because they are women. The results of the case, “changed the theory of sex-discrimination for all women.”

Another case, California Federal Savings and Loan Association v. Guerra, helped establish that pregnancy leave policies were not discrimination against men just because biological males couldn’t get pregnant.

Mackinnon writes, “[t]he arguments that won these cases were based on the plaintiffs' lives as women.” Meaning that these cases highlighted the specific harms faced by women in a society that has historically maintained a “hierarchy of inequality.” This hierarchy includes concrete legal and social deprivation on the basis of sex, including “disenfranchisement, preclusion from property ownership, and use as object, exclusion from public life, sex-based poverty, degraded sexuality, and a devaluation of women's human worth and contributions throughout society.”

According to Mackinnon, certain Black feminist thinking brings race and other identity factors into situations where it is non-operational.

“Wasn't Mechelle Vinson sexually harassed as a woman? Wasn't Lillian Garland [a Black woman] pregnant as a woman? They thought so. The whole point of their cases was to get their injuries understood as ‘based on sex,’ that is, because they are women... What is being a woman if it does not include being oppressed as one?”

Mackinnon goes on to point out specific instances where elevation of race as opposed to gender, ended up harming Black women:

When Black Americans earned the right to vote via the 15th Amendment, Black women (along with white women) were still not allowed to vote on account of being women.

When Black American women are sexually assaulted at two times the rate of white women, they are mostly assaulted as women.

When antiracist Black power organizations were formed in the 1960s, they often elevated misogynists to leadership who sidelined Black women activists. For example, Eldrige Cleaver, an early leader of the Black Panther movement wrote, "I became a rapist. To refine my technique and modus operandi, I started out by practicing on Black girls in the ghetto...and when I considered myself smooth enough, I crossed the tracks and sought out white prey."

Mackinnon is not arguing that race is irrelevant to any of these contexts. She says that, "[t]he African American struggle for social equality...has provided the deep structure, social resonance, and primary referent for legal equality." But with the myriad of examples of women of color’s subjugation on the basis of sex, Mackinnon, questions why Black feminists give an easier time to misogynists who share their race than racists who share their gender.

Mackinnon ends her paper theorizing that the unease surrounding aligning with white women by feminists of color at least partially stems from an aversion to being placed in the same category as, “her... the useless white woman whose first reaction when the going gets rough is to cry.” This is not only because aligning with such a trope is undignified, but also because a group that includes men (like Black people), is more easily seen by society as deserving of rights. Thus, “How the white woman is imagined and constructed and treated becomes a particularly sensitive indicator of the degree to which women, as such, are despised.”

Now that we understand Mackinnon’s arguments a bit better, we can see why many of Crenshaw’s students have such a visceral aversion to them, but Crenshaw sees Mackinnon as useful and complementary to intersectionality.

A Woman-centered Perspective

Are Mackinnon’s arguments convincing to Crenshaw? They are at least partially. The history of white feminist erasure of Black women is plain to see. Despite Mackinnon’s attempts to defend herself, Crenshaw finds legitimacy in the argument that Mackinnon can be essentialist. Where Crenshaw takes issue with some of the Black feminists is in what she sees as a double standard.

Antiracist writers often essentialize Black people and white women but are not as harshly criticized. For example, many male antiracists talk about U.S. segregation or racial profiling in terms of what “Black people” experienced, without having to account for the real ways these policies affect Black men and Black women differently. Yet as soon as a white woman tries to talk about the sexism “women” experience, she is reprimanded for not being intersectional and including women of color.

“It is worth thinking about that when women of color refer to ‘people who look like me,’ it is understood that they mean people of color, not women, in spite of the fact that both race and sex are visual assignments, both possess clarity as well as ambiguity, and both are marks of oppression, hence community.”

- Catherine Mackinnon

The Consequences of Difference

The reason Crenshaw is sympathetic to Mackinnon’s argument has to do with how both thinkers understand difference. For Mackinnon, focusing too much on the differences between women may prevent us from thinking up new, women-centric conceptions of equality that could expand rights for everyone (of all genders). Smaller group victories don’t get women as a class closer to eliminating male domination. Without a women-centered view, equality becomes about obtaining the rights men already have, which makes securing female centered rights, like pregnancy leave, more difficult.

Ultimately, Crenshaw’s goal in Demarginalizing was not just to highlight “what difference difference makes” to the specific project at hand. It was simultaneously to argue that fetishizing difference where it does not make a difference can be just as harmful as erasure.

As intersectionalists, we must remember that each issue we analyze is specific and dynamic. To be clear, this does not mean that certain acts cannot be grouped together to demonstrate a general pattern, or that an understanding of historical and social context is not important to your analyses (it is). But any pattern we find “cannot be fully mapped in advance.” She explains:

“Black women were harmed not only when they were forced into sameness, but also when their difference was interpreted as reflecting an experience so different from Black men and white women that they were rendered categorically distinct from them.”

As we think about our own assessments of white feminism or “Karens,” intersectionality calls for analysis of specific situations rather than pre-packaged ideological groupings. If we arrive at a situation with pre-mapped conclusions about the morality of “girlbosses” or someone’s Karen-ness, we may miss the ways in which power operates. After all, does the concept of Karen at least partially let white people who don’t fully map onto the archetype off the hook for systemic racism? What about white men? There is still no agreed upon name for a male Karen. Why?

The work of intersectionality is to analyze the facts and specific harms at hand, and to make a sound conclusion about “what difference a difference makes” to your situation. Focusing on specific, individual actions and patterns of behavior might be able to get us to the truth faster.

Reflection

Read through this article about Away and run your own analysis. Were journalists targeting Korey because she is a woman? How, if at all, does that relate to the specific claims from Away’s employees?

You are a board member of Away. Do you defend Korey’s right to speak out about what she feels is mistreatment? Do you encourage her to step down? Why?

Having read Crenshaw and Mackinnon’s perspectives on feminism and race, what do you think of the term “Karen?” Is it an example of over abstraction, or an acceptable demonstration of a general pattern?

How do conceptions of white women help or harm feminism and the broader project of gender equality? Does the trope of the Karen advance racial equality? How do you weigh the two?

Is the notion of a Karen gendered? Is it possible for gender stereotypes focusing on white women to ultimately harm women of color?

Think about programs focused on female leadership in your workplace. Do you subscribe to the notion that, “The most equal society we can possibly achieve is one where women are allowed to enjoy rights that men already have?” How might thinking about equality from a woman-centered perspective help you create new or different programs around the concept of equality?

*Note: We will be moving the newsletter to a once every two-week cadence. If you have a story to tell and are interested in being a guest writer, email us at intersectionalityprimer@gmail.com.

P.S. This week’s newsletter is dedicated to John Lewis and CT Vivian, two titans of the Civil Rights Movement. We hope their lives and legacies encourage you to find your own “good trouble.”